Synopsis: In this post and a preprint we show that a model trained with large amounts of protein-ligand interaction data collected using DNA-encoded chemical libraries (DELs) can compete with the current state-of-the-art. We generate additional benchmarks and evaluate our flagship model, Hermes, on nearly 14M examples across more than 500 proteins, the largest validation set we’ve seen. Despite being trained on Leash internal data only, Hermes predicts strongly on public data derived from chemical and protein neighborhoods far from the Hermes training set. To our knowledge, this is the first demonstration of a protein-ligand interaction dataset collected by a single group sufficiently large and diverse enough to predict binding interactions on large collections of public data.

These results indicate that scaled protein-ligand data collection – with a particular focus on capturing small chemical changes with outsized consequences, like we do at Leash – is a critical ingredient for model performance to reach beyond memorization. We believe that this offers a strategy to build models that move past the failure modes that have dominated the field and begin to transform how we practice small molecule chemistry.

Paper: https://github.com/Leash-Labs/hermes-paper/blob/trunk/HERMES.pdf

Papyrus validation set: https://huggingface.co/datasets/Leash-Biosciences/papyrus-decoy-eval

MF-PCBA validation set: https://huggingface.co/datasets/Leash-Biosciences/mf-pcba-bind

2001: A Space Odyssey (Stanley Kubrick and Geoffrey Unsworth, 1968)

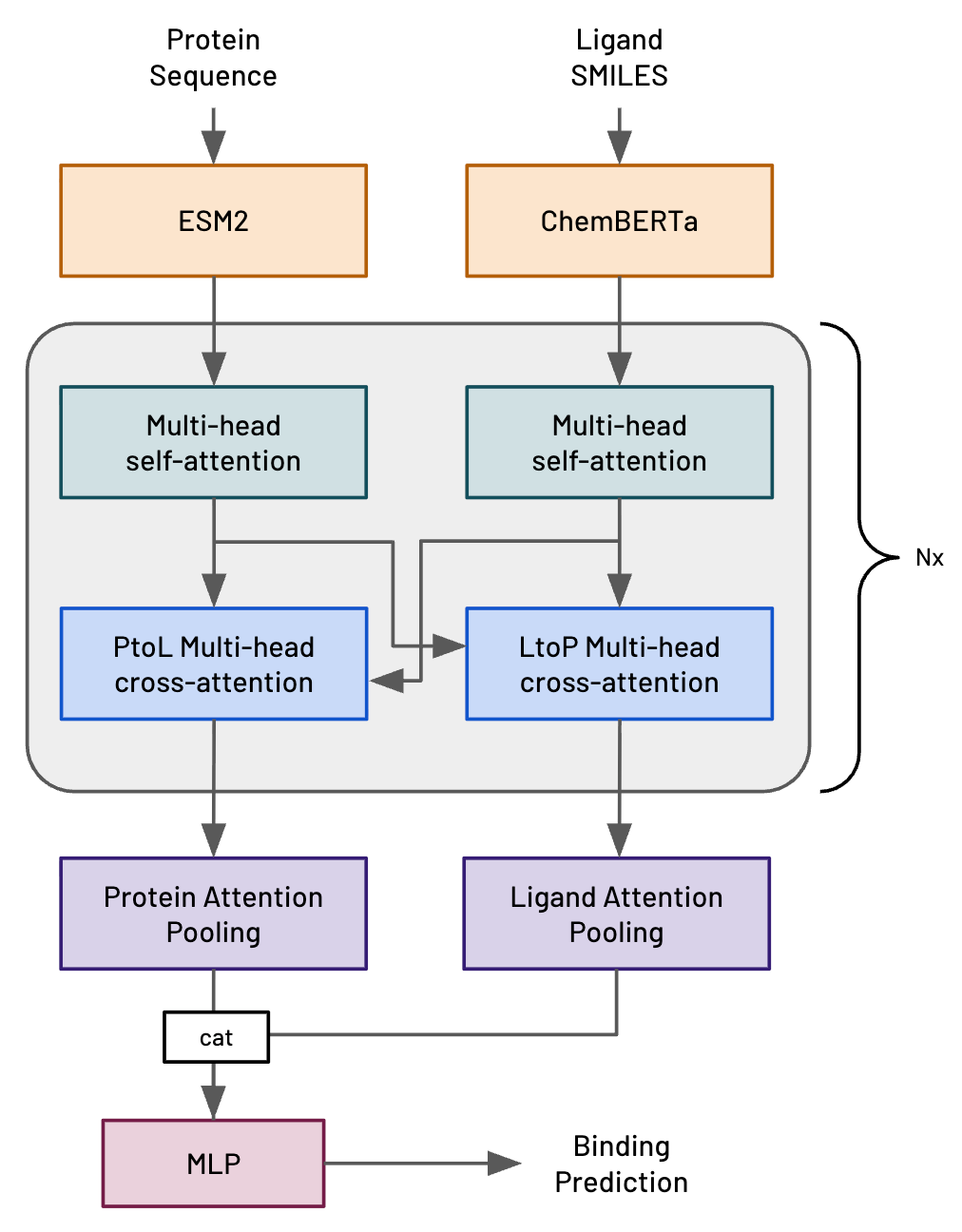

About half a year ago (July 2025) we first described Hermes, a very simple transformer-based model architecture that we’d invented here at Leash (fig 1, ref 1). Hermes is intended to predict the likelihood of a protein-ligand interaction (PLI), where the ligand is a small molecule. We very explicitly designed Hermes to be modest and fast in order to evaluate different training regimes; we never intended it to be competitive with modern, structure-based methods.

Figure 1. Hermes architecture.

We then put together benchmarks of PLI interactions from public data (our original version is here but we encourage you to use the updated one here) and internal Leash data (the strategy to make the Leash benchmark is described in ref 2) and quickly put out some results on Hermes performance (ref 1) , where we showed some glimmers of PLI prediction generalization. We didn’t feel those glimmers were strong enough, though, so we rolled up our sleeves to kick the tires on Hermes a lot more and put the results in a preprint we’re releasing today (ref 3).

Leash data enables predictions into novel chemical space

Our new Hermes findings suggest two things very strongly: 1) with the kind of data we collect here at Leash, one can generalize predictions into new chemical and protein space, and 2) the collection of that data is truly scalable. Put together, we interpret this as an invitation from nature to increase the pace and the diversity of the data we’re collecting.

We’ve brought a lot of attention to problems of bias we see in the field, and we get that such a stance can make us look like downers. Today is different: those problems haven’t gone away, but for the first time we got a glimpse of the way out. The way out is through more data, generated thoughtfully with deep knowledge of how biology works. We no longer believe the way out is through more data just because that’s how a lot of other machine learning problems were solved; we now believe it because we have evidence that more data helps predicting PLI, too, starting with larger numbers of a particular protein family.

Hermes is a tiny, simple model. It has no business trying to compete with the state-of-the-art. We did not intend it for this purpose; it doesn’t have a way to think about protein or molecule structure at all. Yet, it holds its own, and we think it can do that because of the massive amounts of high-quality Leash data we’re able to train it on.

We are not claiming Hermes is a better model - far from it - but what we argue here is 1) even a dinky model like Hermes can obtain modest generalization when given data like what we are generating here at Leash, and 2) generating that data is enormously scalable.

We would also add 3) we feel good about these results because we obtained them by testing hundreds of proteins and millions of molecules in a way designed to minimize leakage (to Hermes).

If you’re a technical person, read on. If you want to skip the nerdy stuff, head on down to The Takeaway.

Hermes is competitive with last week’s state-of-the-art

As we were writing this post over the weekend, we were comparing Hermes performance to that of Boltz2 (ref 4), which, at the time, was the state-of-the-art. Hermes and Boltz2 were within spitting distance across most of our validation examples, and even then, Boltz2 may had seen some of those validation examples or material like them during training. We ran Boltz2 directly on our validation sets and so can evaluate performance against Hermes honestly and go into some detail on those validation examples and Hermes/Boltz2 performance below.

We can’t tell if Hermes is competitive with this week’s state-of-the-art

On Tuesday of this week (10 February 2026), Isomorphic dropped a report on their modeling progress (ref 5), which may well be the new current state-of-the-art. This progress included strong advancements in pose and pocket prediction - Iso called these results a “step change”, and we think that’s right - and it also included results on affinity prediction. Since we don’t have access to IsoDDE, their new pipeline, we can’t make honest comparisons. (To be fair, nobody else has access to Hermes; we’re trying to mitigate this by releasing many of our validation sets publicly.)

To test affinity prediction, Isomorphic uses a “time-split” version of ChEMBL, where PLIs that are new in version 35 of ChEMBL and not present in ChEMBL 34. We’re not exactly sure what’s in that set but we have an upper bound on its size. We do not know what’s in the Isomorphic training set other than the PDB, but given the time-split choice we wonder if examples from earlier versions of ChEMBL may be present.

Time-split validation sets are a problem

We published a paper in December showing that models can identify the creator of a molecule and then use that information to cheat (ref 6, ref 7). We also showed that the usual methods of splitting by structure are unlikely to defeat this bias. By using a time-split approach, it is very likely that chemists contributing to the old ChEMBL have material in the new one, which affords wonderful opportunities for cheating. It would be interesting to see which chemists are in the IsoDDE and the Boltz2 training sets here. The greater the chemist overlap between the time splits, the greater the cheating potential.

Small validation sets are a problem

We run a lot of validation sets here, and we honestly don’t think the ones we have are nearly big enough. We see a lot of variation in performance depending on the presence of key chemical motifs, protein splits, all sorts of stuff. We have ~500 proteins and ~14M molecules in the validation sets in this work and we want a lot more than that. For the Isomorphic work, our quick-and-dirty estimate of ChEMBL 35 gives about 400 unique new proteins and about 65k new molecules. Even if all of those are included, it’s not many. There are 10 targets used in the MF-PCBA validation efforts in the Boltz2 paper, also not many.

Why we think our validation sets are less likely to have leaks for our models

Our chemical material doesn’t look anything like the material in public data. We have our own Leash-designed chemical libraries (they’re DNA-encoded libraries, or DELs) and we make and screen our own proteins with them.

Being so different is good. We recently showed that all chemists (at least, the 1815 chemists we scraped from ChEMBL) have distinct signature styles that models can learn and cheat off of (ref 6, ref 7). So when we trained Hermes, we trained Hermes only on Leash chemistry, nobody else’s, and that gave it fewer opportunities to cheat. Then we used Hermes to predict binding/not-binding for all PLIs in the following sets.

- We took 164 proteins screened against internal Leash chemistry and asked Hermes to predict which Leash chemicals bound to them. Hermes had seen the molecules in the context of other protein targets but not these ones. This is the “DEL Protein Split” and is about 0.2M examples.

- We took a brand-new external chemical library (it looks like the one in ref 8 and nothing like internal Leash chemistry) and screened it against 59 proteins Hermes had seen (but only against internal Leash chemistry). This is the “DEL Chemical Library Split” and is about 3M examples.

- We took a subset of ChEMBL (called Papyrus++, ref 9) and combined it with decoys from GuacaMol (ref 10) to produce a validation set. This is “Public Binders/Decoys” and is about 2.8M examples. That validation set is available for download here.

- We took an existing public set, the Multifidelity PubChem BioAssay collection (ref 11) and used a large portion of it. This is “MF-PCBA” and is about 7.7M examples. That validation set is available for download here.

All together, this is about 515 targets and 13.7M examples.

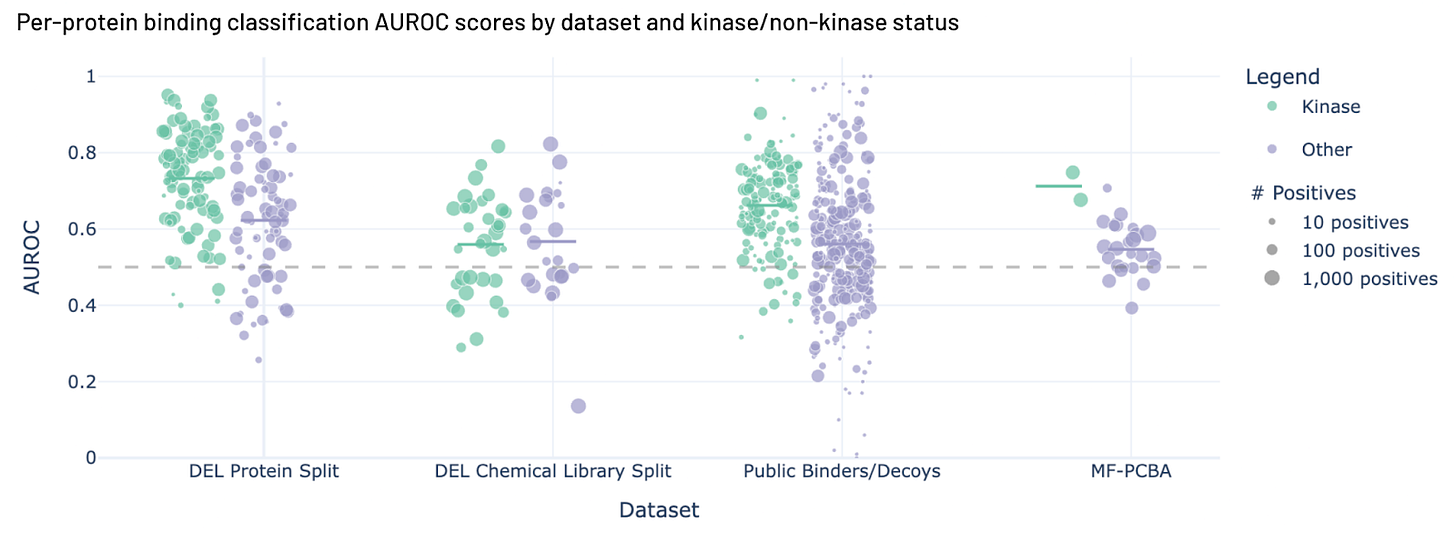

Figure 2. Hermes performance across four benchmarks.

Hermes performance

A quick note: we used Area Under the Receiver-Operator Characteristic (AUROC, explainer here) to evaluate model performance. A big reason we did this, rather than something like Mean Average Precision (mAP, sort of the area under the precision-recall curve, explainer here), is because different proteins had different ratios of positives and negatives, and we wanted to compare them with a consistent baseline.

You can see the results in figure 2. Hermes performs reasonably well on 3 of the 4 challenging benchmarks here, and has positive predictive value for all of them. We want to emphasize that these results are from a model trained with a dataset with far fewer examples than we have now, and that we have put a lot more effort into engineering hard negatives (ref 12) recently, which seems to boost performance.

You may also note that Hermes does better with kinases than non-kinases.

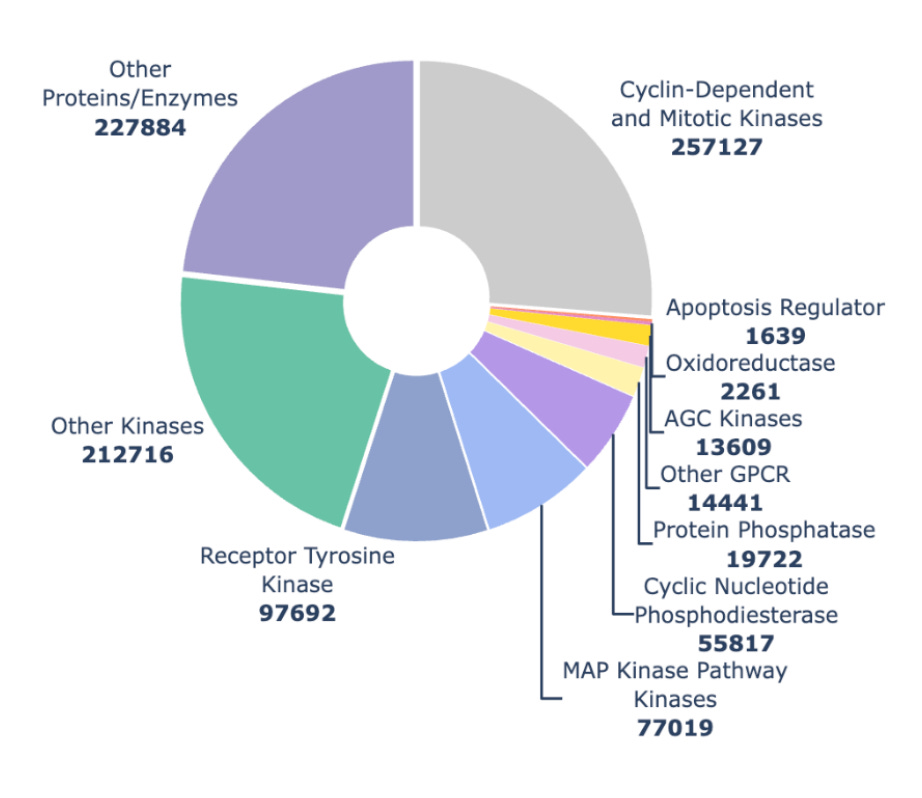

Figure 3. Distribution of examples across protein families and subfamilies from the Hermes training run reported here.

You see more members of a protein family, you can predict on that family better

When we trained Hermes for this work in July 2025 we had a lot of kinase data (fig 3, now kinases make up somewhere between a quarter and a third of our data). We think the larger number of examples helped Hermes understand kinases better, and when we look at how Hermes performs across many different validation sets, it does better on kinases than non-kinases 3 times out of 4 (fig 2).

Hermes beats memorization baseline on public data

We love XGBoost (ref 13) because it’s a simple baseline model that is great at overfitting. We note how few papers in the field use it as a baseline, and that makes us sad. It’s tempting to want fancy architectures, but if they don’t beat tree-based methods like XGBoost, why pay for GPUs?

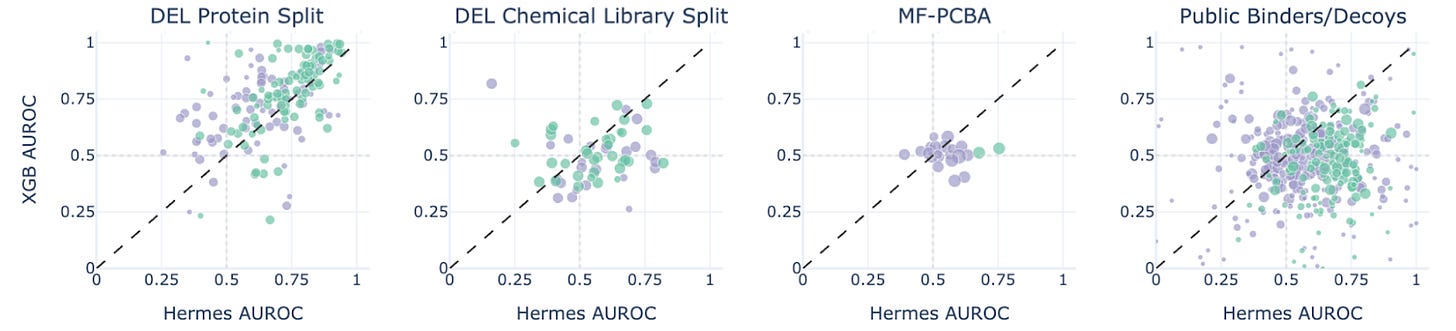

Figure 4. Hermes performance compared with XGBoost performance on four benchmarks.

XGBoost beats Hermes on the protein split, where we test the models on new proteins that have seen internal Leash chemistry, suggesting a data leak (we found one: promiscuous hits that are both in test and validation sets against related targets). But Hermes beats XGB on the other 3 sets, most impressively on the ChEMBL-derived Papyrus set (figure 4). We take this as a hint of generalization.

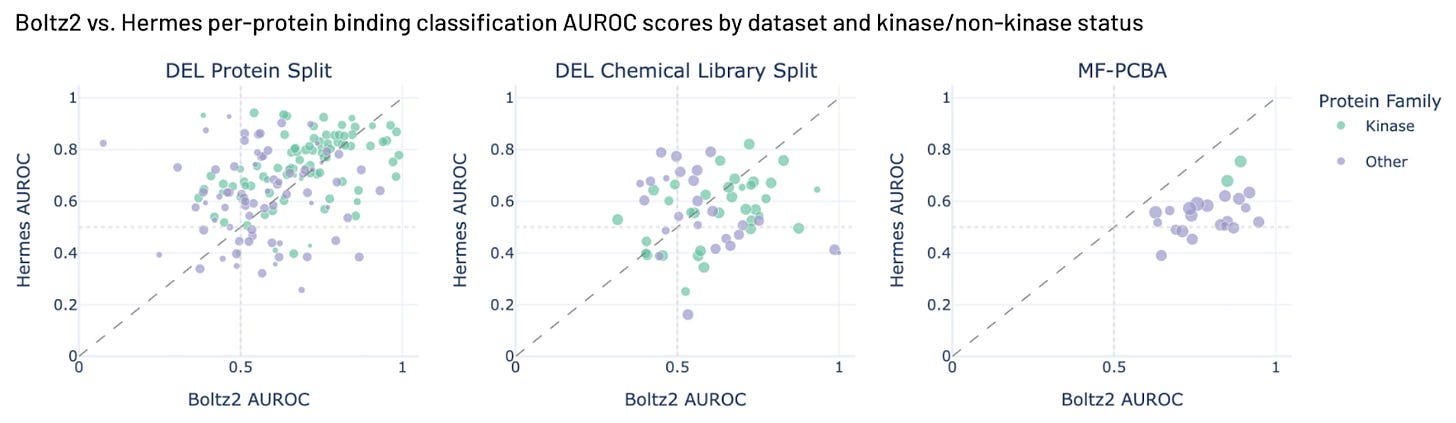

Hermes vs Boltz2 in detail

We ran Boltz2 against our internal benchmarks and MF-PCBA. (We skipped Papyrus, because Boltz2 was probably trained on it.) We see Hermes does slightly better than Boltz2 on Leash chemistry, and Boltz2 does better than Hermes on MF-PCBA. Our set here includes more MF-PCBA examples than Boltz2 reports in their work. Boltz2 could be great at that subset, and it’s also possible that we expanded our examples into their training set, since we use more of MF-PCBA than the Boltz team did. We note that Boltz2 performance on Leash internal chemistry suggests some level of Boltz2 generalization, something we did not see in our earlier Hermes blog post with a much smaller validation set.

Both models do pretty poorly on the new chemistry from Leash (DEL chemical library split). We think we know why Boltz2 does get a perfect score on one outlier target in the DEL chemical library split, though. It’s BRD4, and the chemical library used for that validation set was used to drug BRD4 (ref 8), and there are cocrystals of molecules from that library in PDB already (ref 14). It is gratifying to see Boltz2 accurately predict an example we generated experimentally. There are a total of 661 BRD4 structures in the PDB with 582 ligands; we bet Boltz2 is awesome at BRD4 with common chemistries. Our DEL Chemical Library Split is mostly a replication of a GSK library (ref 8), so other molecules from it might be in public training sets.

To re-emphasize: Hermes is a tiny, simple, model, and only trained on data that we experimentally generated ourselves, yet it is competitive when evaluated against (last week’s) state-of-the-art with enormous and diverse test sets.

Figure 5. Hermes performance compared with Boltz2 performance on three benchmarks.

The Takeaway

How can you tell what’s good?

We are always thinking about models cheating over here. We feel the long-term promise of modern machine learning methods is undercut when cheating models convince all of us that they’re better than they really are - and about a month ago we published work showing that chemists have such a distinctive chemistry style that models can cheat off the style rather than learning the physics of small molecule binding (ref 6, ref 7). So-called “shortcut learning” of this kind is a fundamental and commonplace stumbling block in the way of applying machine learning to many of our most critical biological questions.

Aggregating datasets from many chemists with distinctive styles is exactly the kind of data you get when you train on ChEMBL, and what you might also get from legacy data in private hands – the training data used by the majority of teams building models for PLI. This cheating is very challenging to discover if you train on such data and test on molecules made by chemists in your training set. If your model knows what active molecules from a particular chemist look like, it’s pretty easy for it to pick similar ones out of a validation set lineup without ever having to understand binding physics.

To avoid being misled during evaluation, we think you need at least some molecules made by chemists not represented in your training set (with different signature styles) and good binding labels. We think you need a lot of labels, and maybe a lot of signature styles too. For a trustworthy appraisal, we think you need more than anyone’s shown so far.

Massive data collection, with an eye towards eliminating bias, is going to revolutionize predictive chemistry

To our knowledge, this is by far the largest and most diverse set of validation examples publicly evaluated by any computational PLI study.

Moreover, to our knowledge, this is the first demonstration of positive prediction of binding interactions on large public collections by a model trained solely on data generated experimentally by a single group.

Lots of people we talk to bag on the DEL technology we use here. “Too noisy,” they say. “Not reproducible.” “False negatives!” It is not clear to us that other methods are any better (the compound mislabeling rate of chemical libraries with one tube per molecule has been reported to be as high as 30%, ref 15), and none are as scalable. As our work shows, models trained on quality DEL data are capable of generalizing to non-DEL corners of chemical space.

We make comparisons here to Boltz2, and want to emphasize that we think it and similar approaches championed by our colleagues (IsoDDE, Neuralplexer, Neo-1, OpenFold, and others) are fantastic. To make truly programmable molecular matter, we believe a way forward is coupling such structure-informed models with more and better data and evaluating with more and better benchmarks. Such methods will really sing when they’re trained on the right collection of quality examples like the ones we obtain at Leash. We believe intentionally engineering activity cliffs from both the protein and small molecule sides will be critical.

Ultimately, what excites us most about this work is not the performance - there’s still some way to go, and we have a lot more protein and chemical space to examine - but that there is a clear, tractable, scalable path to truly excellent binding prediction. We’ve more than doubled the number of targets screened since the version of Hermes in this work was trained. The data generation engines built by us and others, properly applied, are gonna crack open PLI prediction in no time. Let’s get to work!